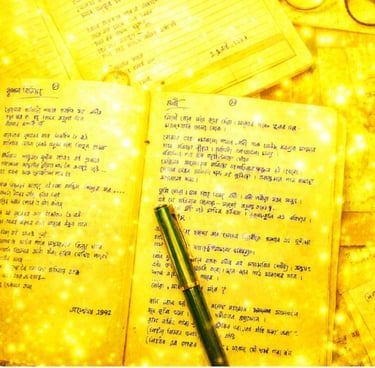

The Journey

We walked on

along the river’s course

The road refused to turn.

In the blurred hush

of a dream-city

we drifted along the wharf,

searching for youth—

for its poise, its ease.

Time had slipped away.

The birds were gone,

their wings once painted with colour.

We grew sullen.

On slate-grey stones

we scratched

the names of trees,

the scent of flowers….

Slowly,

we became images,

fixed and wordless

in the river’s depth.

What were we after—

a reckless evening,

the shoreline of a restless heart

whose dreams keep colliding

with death?

We met a merchant.

His trade was words.

Human, a pilgrim….

Calling the river and its current

by whatever name becomes remembrance.

One who knows

how to make memory beautiful

is a magician:

And what, in endless conflict,

truly endures?

We walked on

along the river’s course.

There were the days,

there must have been moments—

that stayed with us as song.

When the performance ends,

we step further into the river,

second by second.

Days belong to time.

Time—

To whom does it belong?

If you meet youth,

ask it.

________________________

3 May 1993

First published: Pashek, 1993

Editor’s Note

“The Journey” is a meditation on movement without destination. The river here is not merely a natural image; it becomes time itself—unceasing, impartial, and absorbing everything in its flow. The absence of a path suggests a world that resists settlement, where searching becomes more urgent than arrival.

Youth is not presented as a state one attains; it appears instead as an absence—something sought at the riverbank, carved into stone, submerged in memory. The poem suggests that youth is not a time that can be recovered; it is a question that continually recedes, locked in a lasting tension with death.

The figure of the word-merchant marks a moral turning point in the poem. Language becomes commerce, memory an art, and naming a method of preservation—one that allows even what cannot be held to endure briefly. The “magician” is not the one who alters reality, but the one who makes memory bearable, shaping it into a survivable form of beauty.

The poem neither seeks nor offers resolution. Instead, like the river, it deepens—moving inward rather than forward. Days belong to time, but time itself belongs to no one. The final question—“If you were to meet youth, what would you ask?”—leaves the poem open, returning responsibility to the reader, where searching itself becomes the only arrival.